12/8/14 – FDR’s Court Packing Plan

December 8, 2014In April 1937, Texas attorney Richard Burges wrote to his childhood friend Hillary Shewmaker expressing doubt over his vote for Franklin Roosevelt in the recent presidential election. On the heels of his landslide victory, Roosevelt announced proposed legislation to change the composition of the United States Supreme Court, a thinly veiled effort to “pack” the court with justices more favorably inclined toward his New Deal legislation. Burges’ letter was in response to Shewmaker’s own impassioned letter expressing her stance “agin” Roosevelt’s sneaky plan. Demonstrating just how vehemently even Roosevelt’s partisans felt about his “Court Scheme,” Shewmaker had saved every daily paper since February 5, 1937, the day Roosevelt announced his plans, and begged Burges to tell her his opinion of it, too. In response, he told Shewmaker that if he had known that the president would make such a proposal, he very well may have voted against him in the November race.

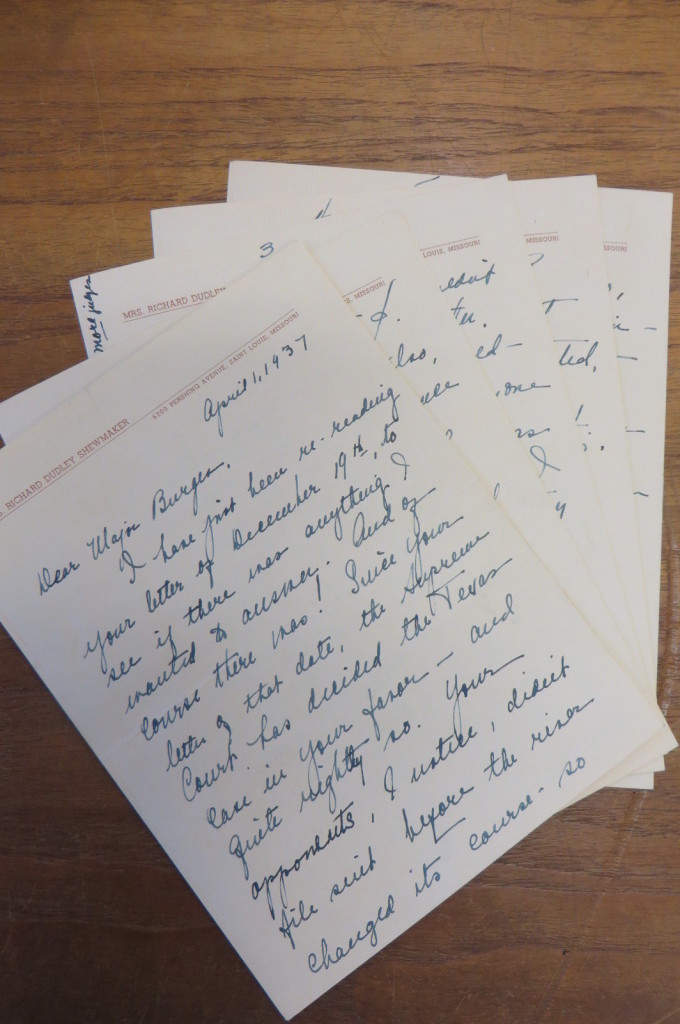

Letter from Major Richard Burges from the Richard Burges Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin.

Today, the court-packing controversy lives on in infamy as one of Roosevelt’s most transparent political efforts to stymy the Supreme Court’s historically firm commitment to private enterprise and limited government. My own fascination with the court controversy stretches back to a class I took with legal historian Laura Kalman in the 1990s. The audacity of Roosevelt’s proposal, the questions it raised about the Constitution and the politics of law spoke volumes about the pivotal era during which Roosevelt governed. Last month in the archives at University of Texas, I was re-invigorated by the subject when finding this exchange of letters.

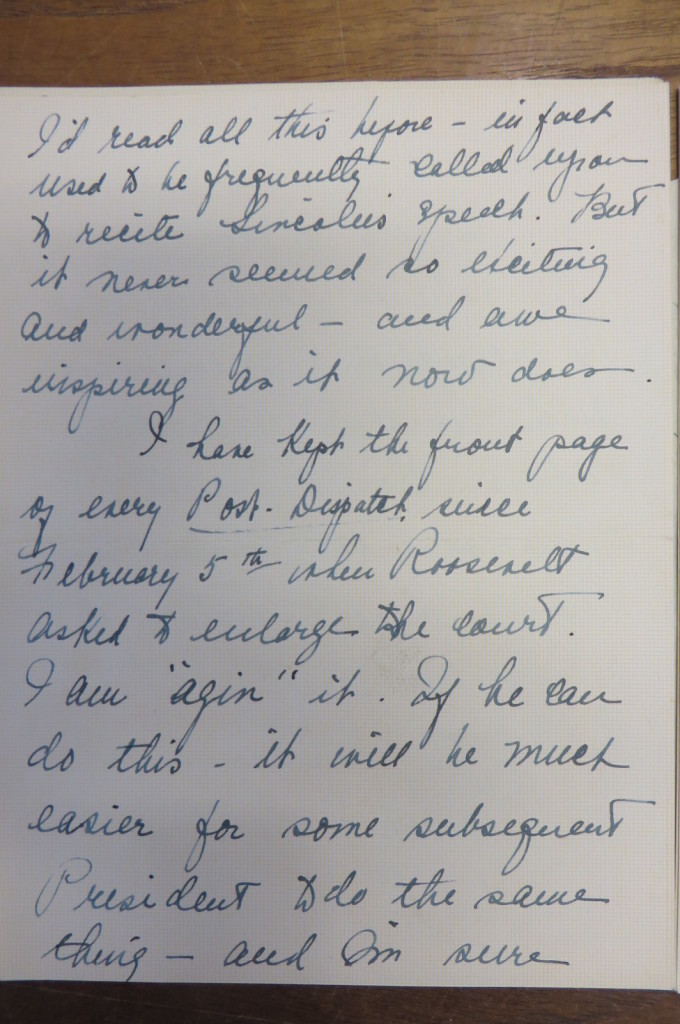

Excerpt from Hillary Shewmaker’s April 1937 letter to Richard Burges from the Richard Burges Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin.

Roosevelt was elected to the presidency in 1932 with simultaneous fanfare and solemnity. On the one hand, loyal partisans were thrilled to take back the White House after so many years on the outside. Democrats had managed to steer only two presidential candidates to victory since the Civil War: Grover Cleveland, whose second administration ended in 1897, and Woodrow Wilson, whose administration ended in 1921. Therefore, Roosevelt’s ascendancy to the oval office was heralded as having great promise for the people of the United States who were suffering through the depths of the Great Depression. Many Americans blamed years of Republican-led, pro-business policies for the economic woes of the 1930s; in their minds, Big Business’s grip on politics and the economy was entirely the fault of the GOP.

Major Richard Burges, a lawyer in Texas, was one of the loyal partisans who quite literally adored Roosevelt and had high hopes for his presidency. Roosevelt obliged such supporters from his first days in office, proposing and shepherding myriad pieces of legislation through Congress that were designed to ease the financial burdens of Americans. His experimental approach to the “first hundred days” in office has had long-lasting impacts on subsequent presidential administrations. But by the start of Roosevelt’s second term, the U.S. Supreme Court had issued several adverse opinions that struck down critical pieces of Roosevelt’s New Deal. How Roosevelt dealt with the opposition – known as the “court packing plan” – made people like Richard Burges question the president’s motivation.

Letter from Hillary Shewmaker to Major Richard Burgess from the Richard Burges Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin.

Despite the commonly held belief that the Supreme Court has always been comprised of nine justices, the Constitution actually left the Supreme Court composition open for lawmakers to decide. Congress’s first law addressing the issue came in 1789 with the Judiciary Act, in which lawmakers set the number of justices at six. From that time until the close of the Civil War in 1865, the number of justices changed six times, ranging from five to seven to ten and finally settling to nine in 1869. Roosevelt’s plan would permit the appointment of up to six new justices for each justice over seventy years of age who declined to retire. This formula would have allowed him to change the existing Court’s composition to gain the majority he needed for decisions that would affirm his legislative agenda.

But an apparent about-face by sitting Justice Owen Roberts seemingly rendered the plan unnecessary. Roberts’ critical swing vote in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish was a stamp of approval for Washington state’s minimum wage law, steeped in the labor reforms of the 1930s that Roosevelt had led. Then, within two weeks, the Court handed down five additional decisions that upheld the constitutionality of a key piece of Roosevelt’s New Deal: the National Labor Relations Act, with Roberts voting with the majority each time.

Roosevelt’s court plan soon died when it became clear that Roberts had switched his allegiances with regard to the constitutionality of New Deal legislation, a switch that has historically been described as “switch in time that saved nine.” What remains a controversy among historians is what exactly led to Roberts’ change of heart. Did he change direction in order to lead the Court away from a direct confrontation with the president who had just scored a landslide victory at the polls? Or were Roberts’ previous votes misconstrued in some way, as he made a gradual intellectual shift toward supporting more intense government intervention of the New Deal kind?

Scholars today agree that historians’ simple explanations of the past are no longer valid. Statistical analysis of Roberts’ previous decisions show that he had been undergoing a conservative shift before the 1936 elections, and underwent a significant but temporary liberal shift after that election before shifting conservative again following the midterms in 1938. In any event, the plan died but not before dampening the spirits of diehard supporters like Richard Burges and his friend Hillary who began to question Roosevelt’s morals and their own supportive votes.

Thanks to the essay “FDR’s Court-Packing Plan: A Study in Irony“ by Richard Menaker for helping with some of the facts in this story.

– Jennifer Stevens

Editor’s Note: Like our features, but looking for a shorter read or more frequent posts? Try our “Vignettes” series by clicking “Vignettes” under the “Categories” in the left navigation bar.

_______________________________________

Sources consulted:

“Supreme Court mystery unlocked from BYU’s vaults 75 years later,” Deseret News via news.byu.edu on September 6, 2012

“Did a Switch in Time Save Nine?” Daniel E. Ho and Kevin M. Quinn, via law.yale.edu, July 10, 2009

“The Switch In Time That Saved Nine: A Study of Justice Owen Roberts’s Vote in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish,” Brian T. Goldman, via repository.upenn.edu, January 1, 2012

“FDR’s Court Packing Plan: A Study in Irony” by Richard Menaker, via gilderlehrman.org