12/9/15 – The History of the War Assets Administration

December 9, 2015On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan’s naval and air forces of attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, a date that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt exclaimed “would live in infamy.”[1] He quite accurately anticipated that this event would mark a pivotal moment in American history. In commemoration of that date, this week’s blog provides a glimpse into one of America’s less-known World War II narratives. And what this story lacks in infamy it easily makes up for in obscurity.

Scholars have studied the history of war from many angles. They have researched and written on the geopolitical events that led to war; war-time ideologies and propaganda; military tactics and technology used in battle; and the environmental impact on the land. The aftermath of war is also a topic of interest for many historians. Some look at how cities that fell-victim to attack worked to rebuild their infrastructure and strengthen their economies, while others analyze the human aspect of war, such as survivor trauma and human cost of war.

History books tell, in gripping detail, about modern “war efforts” of World War II that include communities coming together in the 1940s to conduct scrap metal drives and grow victory gardens. These books typically have a subsection denoted to the historic narrative about women entering the workforce, complete with an image of Rosie the Riveter. All of these historical angles have entered the overarching World War II narrative with which Americans are most familiar.

Although historians tell the story less frequently, the story of postwar economy planning is “riveting” in and of itself. Did you ever consider what happened to the physical remnants of war – the actual physical materials that were either made as part of the war effort but never used, or were acquired during the war? Or consider the history of the war-time surplus? The general absence of this part of the story in most history books is not an indication that such thoughts were not the minds of officials in Washington. If anything, the opposite is true.

Americans conducted scrap-metal drives as a means of contributing to the war effort at home. Source: Library of Congress.

As early as 1941, the Business Advisory Council of the Commerce Department established a Committee on Economic Policy to “consider problems of post-defense-build-up reconversion.”[2] Within a year, Congress formed the Committee for Economic Development as a partnership between academia, business, and government. It was this department that had, by 1944, completed a study outlining the types of surplus expected, as well as a plan as to what to do with such items. The work of these committees and departments prepared President Roosevelt to create the Surplus War Property Administration on February 18, 1944.[3] This agency soon became known as the War Assets Administration and was tasked with the disposal of war surplus, under the guide of the War Property Act of 1944.

FDR was the 32nd President of the United States and created the War Assets Administration on February 18, 1944. Credit: The Maui Almanac

The fact that the United States came together during World War II to manufacture planes, ships, guns, and ammunition with little advanced notice was a remarkable feat; but the government’s disposal of these items was equally astonishing. This was especially true considering the requirements of the War Property Act, which was intended to ensure the most effective use of surplus for common defense. But lawmakers also aimed to aid in the reestablishment of a peacetime economy, to encourage free enterprise and discourage monopolistic practices, to preserve the competitive position of small business, to develop new independent enterprise, and to obtain, for the government, “the fair value of surplus property” upon disposal.[4] This mission was made even more complicated when the amount of surplus to be disposed of numbered in the millions and included typical wartime materials in addition to items such as folding chairs, G.I. socks, tubes of toothpaste, and homing pigeons.[5]

Great Britain also faced a surplus problem. Pictured here are motorcycles that were commandeered as part of the war effort. Many of these were sold or returned to their original owners after the war. Credit: Aaron Cortez, The History of Military Motorcyles.

Many of these items were purchased by Hollywood, especially the planes and other combat equipment. These items graced the silver screen in the many war films that debuted in the 1950s. Soldiers also purchased items as a means of remembering their time in the service. Engineers with the U.S. Geological Survey even asked to purchase prefabricated houses from the WAA that were used to house prisoners-of-war; the asking price for these items was roughly $300.00.[6]

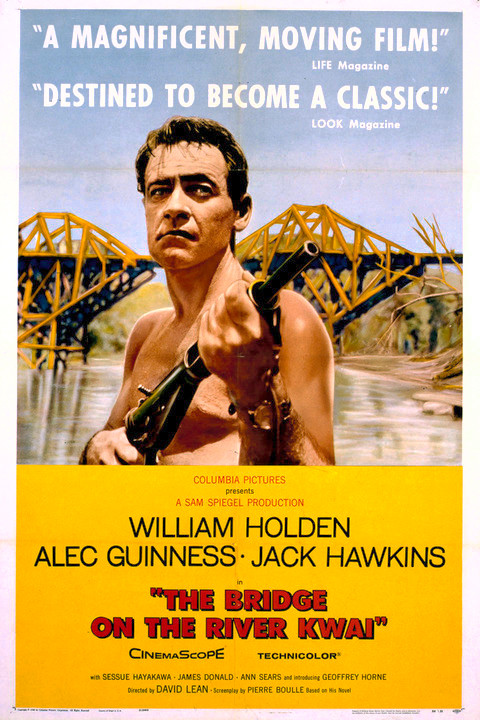

The American film, The Bridge on the River Kwai, released in 1957, was one of many movies released in the 1950s whose plot centered on WWII. Credit.

In all, the WAA sold $34 billion worth of wartime surplus, which in today’s currency equates to nearly $363 billion dollars.[7] And yet, the history of the agency responsible for completing such a daunting task and recouping such a staggering amount of money rarely appears in the multitude of history books about World War II. Although this blog has only skimmed the surface of this agency’s history, I hope that it will pique the interest of historians, scholars, and our learned readers to dig further into this story.

– HannaLore Hein

_______________________________________________________________________________

[1] Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York. http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5166

[2] Louis Cain and George Neumann, “Planning for Peace: The Surplus Property Act of 1944,” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 41, No. 1 The Task of Economic History, March, 1981: 130.

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid.

[5] James R. Chiles, “How the great war on war surplus got won or lost: getting rid of $34 billion worth of old ships, plane and guns, not to mention seven million tubes of toothpaste, was no picnic,” Smithsonian Magazine, December, 1995.

[6] Records of the Geological Survey, R.G. 57, Administrative Records – Water Resource Division, 1919-1951.

[7] http://www.usinflationcalculator.com/